At some point in a 20-minute nature walk that ended up being a 10-kilometer trek around Uganda’s Lake Bunyonyi, Hillary Smith had a public health epiphany: “If you look too far ahead you can get overwhelmed by the journey, but taking it one 20-minute nature walk at a time you will end up accomplishing far more than you ever thought possible.”

She was completing her MPH practicum experience with the Global Livingston Institute in Uganda last summer when she and another intern set off to conduct public health surveys at a nearby village. Rogers , a staff member at the Entusi Retreat and Resort Center where Hillary was based, offered to go along as a translator and promised the “20-minute nature walk” to get there. Ten kilometers later and thoroughly exhausted, she asked Rogers why he didn’t mention the actual distance.

“He said, ‘You never tell someone how far they are going to go when you start, otherwise they will never make it. But, look how much you have accomplished thinking you were only going on a 20-minute nature walk’,” she recalled him explaining.

It was a valuable lesson that translates to the work and practice of public health, one that Hillary crossed an ocean to learn. She was one of four ColoradoSPH at CSU students who traveled to Uganda over the summer to complete their practicum experiences or capstone projects, or both, working on projects that varied from testing expectant mothers for hepatitis B to dosing farm animals with anti-parasitic medication.

Practicing One Health in Uganda

Isabella Mazariegos, who is studying in the MPH/DVM program, worked with Conservation Through Public Health in Buhoma, which is next to Bwindi Impenetrable National Forest where the endangered mountain gorillas live. Her work included taking fecal samples for parasite analysis in the lab, giving anti-parasitic medications and going to schools to give gorilla conservation talks to the children and going into the forest to collect gorilla

fecal samples.

It was a summer of firsts: first time injecting a goat, first time seeing mountain gorillas in their natural habitat – “I stood next to them for hours watching them eat and interact with each other. I was fascinated by how similar they are to us – I could’ve stayed there all day. It was magical,” she remembered. It also was a summer that strengthened her passion for the One Health approach to public health practice.

“I learned that human health is very interconnected to animal health, especially in areas where livestock, wildlife, pets and humans all live in very close proximity to each other, like they do in this part of Uganda,” Isabella said. “I learned the importance of keeping human populations healthy to not affect the animals, and vice-versa.”

For Amanda Tyler, working with Uganda Village Project in Naluko village in Uganda’s Iganga district was an opportunity to conduct house-to-house surveys that she and the rest of the team with which she was working used to develop educational learning processes for the community. Following that, she and the team carried out those processes regarding HIV, malaria, family planning, WASH (water, access, sanitation and hygiene), obstetric fistula and adolescent reproductive health.

Lessons of public health

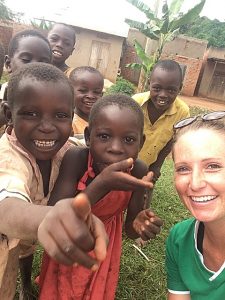

While Amanda loved the fun times of playing soccer with children in the village, who called her and the other foreigners “muzungos,” and exploring that region of Africa, it was attending two funerals during her time there that had a profound impact.

“There are still things that go on that are out of our control and sadly a normal part of life for many people living within the village,” Amanda explained. “People passing away as frequently as they do in the village should not be ‘normal’ and it made me realize the importance of public health work, and that hopefully what we did while there and what (Uganda Village Project) continues to do will have an impact on life expectancy.”

Jackie Williamson came to similar insights while working with the Foundation for Community Development and Empowerment in Kasese. Among the projects on which she worked was collaborating with the established Young Mother’s Group of Rwenzori Rural Health Services to teach educational songs and skits about family planning methods. Ultimately, she helped develop an informational reproductive health program to increase the awareness of women’s reproductive health and services.

“These women were originally very hesitant to the information I provided surrounding reproductive health and family planning,” Jackie recalled. “I was able to make personal connections with these women and consequently adapt my program to better serve their needs.

The overarching lesson of her time in Uganda, Jackie said, “is the importance of utilizing human resources and human capital and being adaptable to cultures so different from your own. My success in my projects in Uganda relied entirely upon trusting and allowing the influence from the affected and target communities that I hoped to reach.”

Though they traveled to another continent to do public health in communities quite different from their own, each student said that the lessons they learned about listening, collaboration and community buy-in translate to public health practice both far away and close to home.