Before actually seeing the chickens pecking in the dirt outside brightly painted homes in rural eastern India, Anna Pollard and Kaitlin Dickson, both students in the ColoradoSPH at CSU MPH-DVM program, were only somewhat familiar with avian influenza.

They knew it was viral, they knew it could be transmitted from wild to domestic birds. But it wasn’t until they were in India over the summer and talking with residents of Keranga, a rural village just north of the Chitroptala River in India’s eastern Odisha state, that they began to understand the seriousness of bird flu.

“If you have less than 10 chickens, which most people did, and you rely on them for eggs – if your family is eating them or you’re selling them – it’s a really big deal when even one dies,” explained Kaitlin, a student in the Epidemiology concentration.

Also, though it is uncommon, there have been reported cases in Asia of humans getting bird flu, so a public health risk exists in areas where the virus is present, not much is generally known about it and little is done to prevent or control its transmission. Some people in the area even reported giving diseased chicken carcasses to people living in tribal areas nearby.

Anna and Kaitlin went to Keranga to complete their MPH practicum and capstone projects, both of which are centered on the understanding of bird flu and its physical and economic impacts on people in Keranga and the surrounding area. Looking at the public health impacts of the bird flu, including observation how animals and people live together in that region and the potential for disease to be transmitted between species, transitioned into veterinary research on cattle, which they did in Keranga with with Craig Mullenax, a ColoradoSPH at CSU alumnus in the Animals, People and the Environment concentration and current CSU veterinary student.

Mullenax has extensive experience working with people and animals in that region of India and was able to help guide them toward a research focus, said Anna, a student in the Animals, People and the Environment concentration.

After the outbreak

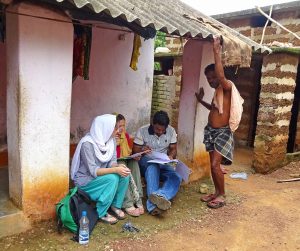

In order to complete as many surveys as possible – they left Keranga with 100 – they rode two hours each way in an open-air autorickshaw to meet with Tulu, their local translator, who introduced them to village residents who kept varying numbers of chickens. They usually drank a cup of chai with each person before asking typical demographic questions and then moving into the focus of their survey: How many birds to you have? How do you use them? Where do you keep them? Do you slaughter them? How do you monitor their health?

Finally, they wou ld ask whether any of that person’s chickens got bird flu during the most recent outbreak in December 2016 to January 2017.

ld ask whether any of that person’s chickens got bird flu during the most recent outbreak in December 2016 to January 2017.

“A lot of the people we talked with had lost chickens,” Kaitlin said. “Some even admitted they’d hid maybe one dead chicken from government inspectors.”

In fact, Keranga became nationally infamous when village residents resisted government inspectors who came to cull birds after the H5N1 virus was detected in Khurda district, of which Keranga is a part, in December 2016. Keranga was deemed the epicenter and government officials came to cull the estimated 2,000 birds in the area. After a 2012 outbreak, about 32,000 birds were culled in Keranga, according to the Times of India newspaper.

“There’s no word in Oriya (the language of Odisha) for bird flu,” Kaitlin said. “They use English and I don’t think it really means anything to them. One person of the 100 we talked to knew it was a virus and nobody knew how it was spread. One guy said it was a government conspiracy because he likes to hunt crows.”

She explained that researchers believe the virus is transmitted from water fowl migrating to Odisha’s rice fields from West Bengal to the wild crow population, who then transmit it to chickens.

Based on their surveys, Kaitlin’s capstone project will be a statistical analysis of the data and Anna’s will focus on formulating an educational agenda for bird flu. Both hope to be able to share their research with government and veterinary officials in the Keranga area, with a goal of helping prevent future outbreaks.